A swirling mist hangs over the winding road ahead, forcing me to slow to a crawl. Just beyond the passenger window, the icy cold torrent of Furebergsfossen waterfall thunders down the fjordside. It’s not the first waterfall I’ve crossed here in the south-west of Norway. The scenic routes that connect Bergen and Stavanger are peppered with photo-worthy cascades, mountain-flanked fjords and tiny timber towns hosting hospitality heavyweights.

Some 30 years ago, komle – a working-class dish of potato dumplings served with salted and boiled lamb, sausages and melted butter – was standard midweek fare. This Thursday evening, I’m seated in front of a sleek open kitchen, watching a chef delicately tweeze ramson flowers onto sashimi mahogany clam. It’s one of five “raw bar” courses highlighting the freshest in Norway’s coldwater seafood. Local bivalves, fish and langoustine feature heavily elsewhere on the menu, playfully paired with more international ingredients like kombu, makrut lime and yuzu. But, the last of the 22 courses – kardemommeboller – is a straight-up ode to Norway, still warm from the oven and braided with fragrant cardamom sugar.

I keep half of the sweet bun for my early morning ferry north, day two of my bespoke culinary-themed itinerary taking me an hour and a half out of Bergen. Fedje Island, population around 500, is the kind of place Up Norway is practised in finding for its guests: off-the-radar to many international travellers but entirely deserving of the spotlight. It’s quintessential coastal Norway, with traditional timber homes teetering on the island’s rocky edge, and small fishing boats bobbing in the ferry’s wake. I disembark in the heart of town, though the term is a bit rich given it’s nothing more than a small supermarket, two eateries, a pub and a distillery.

A group of more than a thousand women owns the distillery, explains Therese Storebø, product developer and brand ambassador at Feddie Ocean Distillery, as she guides me around the barrel store. Once an old marine mechanic’s workshop, the industrial shed is now wall to wall with casks, some ex-bourbon, some chestnut, all imparting their characteristics on young whisky. “Our investors are everything from hairdressers, teachers and doctors, to some of the hardest-hitting women in finance in Norway,” says Storebø proudly. “Feddie works hard on sharing knowledge and teaching women how to invest in other areas.” It’s a big philosophy for a boutique distillery on an island barely discernible on the map.

Naturally, Feddie’s concise portfolio – a four-year-old single malt, two gins and three aquavits – lines the backbar of Pernille and Losen Pizza & Søte Saker, the island’s two restaurants run by chef Moritz Drechsel. A London dry and tonic feels a slightly more elevated beverage pairing than a lager for the crisp-based whale, artichoke and olive pizza he serves. It’s an homage to the whaling industry that once sustained the island, Drechsel reinventing it and bringing it into a more modern context.

My culinary discovery road trip, curated by Up Norway, began in Stavanger, the country’s oil and gas capital, just under an hour’s flight from Oslo. Characterised by a quaint, pub-lined harbour and cobbled streets, it has an unusually high concentration of Michelin-starred restaurants. Re-Naa, the grandfather of fine-dining in Stavanger, is one of only two restaurants with three stars in all of Norway.

“We’re a very young country when it comes to Michelin stars,” says Torill Renaa who, along with her chef husband Sven Erik, has worked tirelessly over the past 15 years to transform the culinary scene in regional Norway. “When it comes to Stavanger, the first liquor license outside of the local pub came in the ’90s. This area was extremely religious, so the development that happened in that period of time is huge.”

Though the fisheries are no longer the island’s bread and butter, it’s an entirely different story in the village of Bekkjarvik. I’ve been connected with Frank Halstensen at Bekkjarvik Experience, who, in turn, has arranged for his childhood friend, Jan Otto, to take me fishing. It’s a rare, blue-sky day, the water mirroring the mountains back at themselves.

We boat between islands, passing floating salmon farms and clocking soaring sea eagles, before dropping lines to the ocean floor. Norwegians don’t use bait, and it appears it’s void anyway. Within a minute, I’m reeling in a quartet of flapping pollock. They’re not the area’s most prized catch – that’d be herring and cod, both of which are fished in commercial quantities – but they’re just the ticket for our lunch of home-style, chowder-esque fiskesuppe at Bekkjarvik Gjestgiveri.

The creamy seafood soup is a Norwegian staple, almost expected on any café menu come summer. But not at Mirabelle, Beckerwyc House’s fine-dining restaurant. “I grew up in Bekkjarvik Gjestgiveri,” says Ørjan Johannessen, 2015 Bocuse d’Or winner and owner of Mirabelle. It’s his parents’ historic hotel just down the hill, to which, with Johannessen’s help, they added Beckerwyc House in 2023.

“In the mornings, my brother and I would fish for crabs. We’d stand in front of the hotel and sell them for 10 kroner.” It’s the childhood memory that inspired one of the five snack courses on his 15-course menu: a delicate crab croustade topped with dill and preserved lemon. From my table, I’m able to see the white timber villa of the hotel and harbour Johannessen speaks of. The uninterrupted view of Bekkjarvik is as much a part of the dining experience as the food.

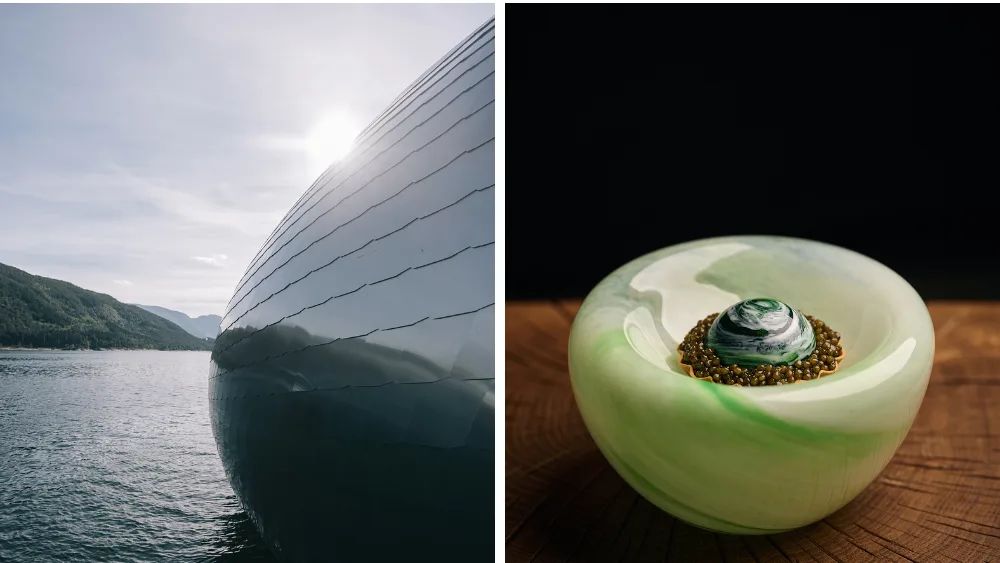

Iris, the Michelin-starred restaurant at Salmon Eye – a futuristic art installation and aquaculture learning centre that floats on Hardangerfjord – takes this concept one step further by incorporating sound, as well as rooftop views, into its third course. Crotchets and quavers wrap around a langoustine tartare-filled shell, shaped to emulate the mountains before us. A musical rendition of the ridge plays beneath the breeze, each peak mapped out on a stave and turned into a haunting tune.

Inside, the soundtrack changes again, its cadence more reflective of the fjord backdrop. They’re equally immersive, both telling the story of threats to the current global food system and presenting chef Anika Madsen’s ideas for combating them. Colourless salmon plays with the senses while offering insight into the artificial colouring of farmed salmon through its feed. And a crisp snow crab blini arrives on the table with a crab-shell-come-lamp to highlight the discard’s battery powering potential.

After such an all-encompassing experience, it’s with full stomachs, hearts and minds that we board a tender back to shore. The setting sun blazes golden, glittering off the scaled exterior of Salmon Eye, as we circle it for one last time. Iris – the final dining experience on my trip – couldn’t be more apt. The ultimate expression of Norway’s flourishing culinary scene, dining on an innovative menu served while bobbing in the middle of a fjord.

Norway is best known for a combination of stunning natural landscapes, rich cultural heritage and high quality of life. Increasingly, Norway is becoming known for its culinary scene, with Michelin-starred restaurants abounding.

Yes, most Norwegians have a reasonable grasp of English, and Oslo in particular is quite an international city with many foreigners also speaking English. You’ll find that you can converse in English in most shops and restaurants, and should be able to get around sufficiently.